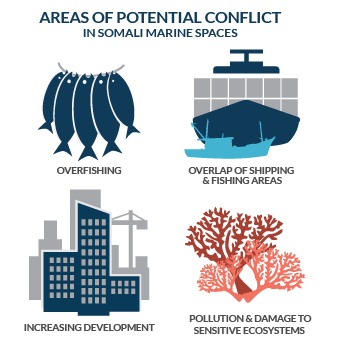

Somali waters support a range of activities including domestic fishing, development projects, foreign fishing, and shipping. Small coastal fishing communities and large urban areas alike depend on coastal resources for food, transportation, goods, and global access. While each activity or resource can be managed independently, a more holistic view of the marine and coastal space illuminates areas where activities overlap, compete, or conflict. As the region’s population grows and the economy develops, activities within each maritime sector will also increase, placing greater strain on resources.

Outlining and understanding these interactions will enable the creation of appropriate management measures that incorporate stakeholder needs, and conserve the coastal space and resources within it for long-term benefit, while avoiding potential conflict. For example, violent clashes occur between foreign and domestic vessels attempting to fish in the same area and for the same species. Shipping could exacerbate these issues if vessel traffic increases and overlaps with fishing grounds to reduce fuel use or transit time, putting shipping vessels in contact with fishers. Over time, these human activities will further impact the natural environment by removing resources, causing physical damage, or polluting the water. Comprehensive management plans that take into account the need to expand the blue economy while preserving the resources that support it will support progress towards a sustainable future for Somalis.

Domestic Fishing

For coastal communities, fishing is crucial to food and economic security, which in turn creates local stability. For Somalis, the exact contribution of fishing to local economies is not currently known, but the sector presents opportunities for growth and expansion, especially through development of the value chain and expanded market access. Long-term benefits from expansion of the fishing sector will involve careful consideration and planning in the context of the other uses of coastal resources and sustainability of the fisheries involved.

Fishing by Somalis is nearly all small-scale and artisanal, conducted in small, open boats with outboard motors. They catch fish and invertebrates close to shore, often in sensitive habitats, using a variety of fishing methods including handlines, pole and line, gillnets, beach seines, and traps. To date, there is little information about the amount of domestic fishing in Somali waters, and this information is needed to assess the current health of the fishery and its ability to withstand ongoing or increased fishing. Data collection mechanisms are needed to understand which fisheries are most important to supporting Somali livelihoods and how they will be impacted by other uses of the marine space. With this information, fish stock assessments and management plans can be created that ensure sustainability of the resources and enable the fishing sector to provide benefits to Somalis over the long-term.

Combining sustainably managed fisheries with a robust and efficient value chain could allow Somalis to capitalize on the demand for fish in the region and internationally. Most of the catch by Somali fishers is landed on the beach then processed and sold to domestic markets. Export to international markets is hampered by a lack of infrastructure, including freezers and reliable access to energy; sanitary processing facilities that meet international standards of quality control; freezer trucks, boats, or planes that could transport the processed catch long distances; and trainings for Somalis in each of these skillsets. Improving each of these areas would enable Somalis to expand the market for their fish and receive greater value for the catch.

Universities Collecting Catch Data

In an effort to begin region-wide fisheries data collection, Secure Fisheries began Project Kalluun, a partnership with four universities in the Somali region focused on training students in marine science and data collection skills. The participating universities are Berbera Maritime and Fisheries Academy in Berbera, Somaliland; East Africa University in Bosaso, Puntland; City University of Mogadishu in Mogadishu, Benadir; and Kismayo University in Kismayo, South West. The goal of the project is to train the next generation of Somali marine science to collect catch data using scientifically rigorous methods, with the goal of establishing a domestic catch database as well as future Somali leaders in marine science. These well-trained students can use their knowledge of fisheries science to further their education in graduate programs and in their future careers. Summarized results of catch composition are visible in Project Badweyn.

Development Projects

International development efforts are an important component for stabilizing the country, building the Somali economy, and improving livelihoods. Because domestic fisheries have great potential to improve local food and economic security, international agencies seeking to fund and implement projects often look to the Somali coast for opportunities. Coordination among groups doing related work is key to maximizing impact and efficiency.

This map of recent and ongoing coastal projects has two main objectives. The first objective is to show the geographic concentrations of development efforts in order to promote collaboration among groups working in the same areas and on similar issues. The second objective is to enable groups that are creating new projects to find places and people with the greatest need and not duplicate other groups’ efforts.

The development groups whose work is displayed here include international aid organizations and non-profits. The projects are primarily capacity building and training, but also include awareness campaigns, habitat restoration, research, and policy development. Projects focus on a wide range of activities and often target especially vulnerable populations such as women, youth, and internally displaced persons.

Foreign Fishing

Foreign fishing has the potential to either exacerbate conflict and deplete Somali resources or support long-term economic security by providing income to the country if licensed, managed, and enforced effectively. Fishers from at least 13 foreign nations fish in Somali waters. They extract three times more fish from Somali waters than domestic fishers, often competing for the same species and fishing grounds. Besides this direct conflict over resources, foreign fishing is a major source of resentment for Somali coastal communities that see foreign fishers as stealing their fish, committing violence against local fishers, and as an example of ineffective governance mechanisms that fail to protect the Somali people. However, if effectively managed in a way that preserves livelihoods, ecosystems, and fish stocks, foreign fishers present an opportunity for increased revenue from fishing licenses and sector economic growth if these vessels can eventually land and process their fish in Somali ports.

The fishery for highly migratory species in the Indian Ocean is extensive and lucrative. Vessels from countries near and far fish for tuna, billfishes, sharks, and mackerels off the Horn of Africa. The area of most intense fishing varies according to season and type of vessel, but one area of high overall catch in the Western Indian Ocean is off the Somali coast.

Sustainably regulating these fisheries both within and beyond the Somali EEZ is needed for lasting and reliable revenue generation. Because these fishes move across country boundaries, catch of highly migratory fishes in the Indian Ocean is managed by the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), a regional fisheries management organization of which Somalia is a member. It monitors catch and assesses the sustainability of each species by collecting and analyzing data provided voluntarily from fishing countries. Currently, many commercially valuable species are being fished at unsustainable levels. These fish stocks may collapse if regulatory measures are not adhered to by fishers, harming the fishing economy of every country that depends on these fisheries and negating the Somali plan for future fishing revenue.

The presence of foreign bottom trawlers (boats that pull nets across the ocean floor, catching everything in their path) and gillnetters (passive nets that entangle fish) has led to conflict. These vessels are larger and more efficient than local fishers, so they are more quickly fishing down the resources that coastal communities depend on for their livelihoods. Trawling requires relatively shallow water. Off the Somali coast, the only areas shallow enough to be fished by these methods are very close to shore, often bringing trawl vessels into contact with Somali fishers.

Foreign fishing vessels have persisted in Somali waters for decades by exploiting gaps in governance. And there is a need for greater enforcement capacity to be able to apprehend vessels fishing illegally. Even where that capacity is strong, some foreign vessels often use tactics to evade law enforcement. They may change their name, flag, and identification numbers; they may not carry tracking devices and if they do, they may tamper with the broadcast information or turn them off entirely to avoid detection.

Combating foreign IUU fishing requires coordination between local communities and national enforcement agencies. Secure Fisheries works to enhance these networks to support a more prosperous Somali fishing sector.

Shipping

The Somali region has long depended on maritime trade as a main driver of its economy. That connection to the rest of the world was cut off during the height of piracy. In recent years though, as piracy has decreased and commerce has expanded, shipping has resurged in the region, especially benefitting the large port cities.

However, this increase in shipping traffic could also cause conflicts. Ships previously avoided transiting close to the Somali coast due to the threat of pirate attacks, but the decline in piracy has allowed ships to come closer to shore to save time and fuel going around the Horn of Africa. This is bringing shipping vessels into areas frequented by foreign and domestic fishers, which could result in accidents or violent clashes, especially when local fishers are mistaken for pirates. Shipping vessels coming close to shore can also threaten the health of the marine ecosystems by causing physical damage or polluting the water. As management plans are created for coastal areas, it will be important to consider discrete, enforceable shipping lanes that allow shipping traffic to flow in areas where they will not compete with fishers or harm natural resources.

Fisheries Conflict

Fisheries conflict is an underappreciated threat to the stability and health of communities. Declining fish populations, rising demand for seafood, and efforts to reduce illegal fishing are increasing the risk that conflict over fisheries resources will undermine stability and peace. The nutrient-rich waters around the Horn of Africa support domestic and foreign fishing fleets that harvest tens of thousands of tons of valuable fish every year. However, low capacity for enforcement of maritime laws since the Somali civil war began in 1991 has enabled illegal fishing while undermining domestic maritime domain awareness.

The data in Project Badweyn show the results of an investigation in the Horn of Africa region in order to add to the limited but growing understanding of the factors contributing to or mitigating conflict over fisheries resources. Conflict was caused primarily by illegal fishing, foreign fishing, weak governance, limits on access to fishing grounds, and criminal activities including piracy. Fisheries conflict events are shown according to their corresponding level of violence. Low-level represents verbal conflict with no physical action taken, such as bans, complaints, and fines. Medium-level events involve action taken (e.g. property damage, gear confiscation, arrests, abductions), but no physical harm. The high-level violence pertains to instances of physical harm (e.g. injuries, sexual assaults, fatalities). By displaying these conflict events alongside the other data in Project Badweyn, decision makers can better understand where conflict is likely to arise and for what reasons, allowing development of policies that mitigate conflict and maximize peaceful resource use.

Go To Project Badweyn Overview and Interactive Map

Data Attribution and License Information

All written content except "Fisheries Conflict" by Paige M. Roberts. "Fisheries Conflict" by Colleen Devlin.

All photos courtesy of Jean-Pierre Larroque.

Landing sites and Ports maps created by Paige M. Roberts. Region names added from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Somalia, License Creative Commons Attribution for Intergovernmental Organisations. Accessed January 25, 2022, https://data.humdata.org/dataset/somalia-settlements-2012

Foreign Fishing Areas – Catch (mt) of Highly Migratory Fishes data analysis by Sarah M. Glaser. Visualization by Paige M. Roberts. Data obtained from Indian Ocean Tuna Commission. “Available Datasets.” Data. Accessed December 9, 2014. http://iotc.org/data/datasets.

Foreign Fishing Areas – Coastal Species data analysis and visualization by Paige M. Roberts. Data for northeast coast obtained from exactEarth, Cambridge, Ontario, Canada. March 26, 2015.

Shipping Traffic Density data analysis and visualization by Brian Free. Data obtained from exactEarth, Cambridge, Ontario, Canada. 2016.

Bibliography

Bell, Curtis, and Ben Lawellin. Stable Seas: Somali Waters. Denver: One Earth Future, 2017. DOI:10.18289/OEF.2017.015. Available at https://oneearthfuture.org/publication/stable-seas-somali-waters

Devlin, Colleen, Sarah M Glaser, Joshua E Lambert, and Ciera Villegas. “The Causes and Consequences of Fisheries Conflict around the Horn of Africa.” Journal of Peace Research. December 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433211038476.

Glaser, Sarah M., Paige M. Roberts, Robert H. Mazurek, Kaija J. Hurlburt, Liza Kana-Hartnett. Securing Somali Fisheries. Denver: One Earth Future, 2015. DOI: 10.18289/OEF.2015.001. Available here.

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission. “Structure of the Commission.” The Commission. Accessed August 28, 2017. http://iotc.org/about-iotc/structure-commission.

Oceans Beyond Piracy. The State of Maritime Piracy 2015. Denver: One Earth Future, 2016. Available from http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/sites/default/files/State_of_Maritime_Piracy_2015.pdf

Sea Around Us. “Catches by Taxon in the waters of Somalia.” Tools & Data. Accessed August 16, 2017. http://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez/706?chart=catch-chart&dimension=taxon&measure=tonnage&limit=10.

University of Rhode Island and Transafrica Consultancy Services LLC. Illegal Unreported and Unrgulated (IUU) Fishing in the Territorial Waters of Somalia. Nairobi: Adeso, 2015. Available from http://adesoafrica.org/newsroom/newsroom/illegal-and-unregulated-fishing-in-somalia-report-2015/.

World Wildlife Federation. “Marine Problems: Shipping.” Threats to oceans and coasts. Accessed August 8, 2017. http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/blue_planet/problems/shipping/.