Although a Cypriot solution negotiated by Greek and Turkish Cypriots may seem virtually impossible. The reelection in February 2018 of Greek Cypriot leader Nicos Anastasiades who along with his Turkish Cypriot counterpart, Mustafa Akınc, has been a longtime proponent of reunification under a bizonal and bicommunal federation.

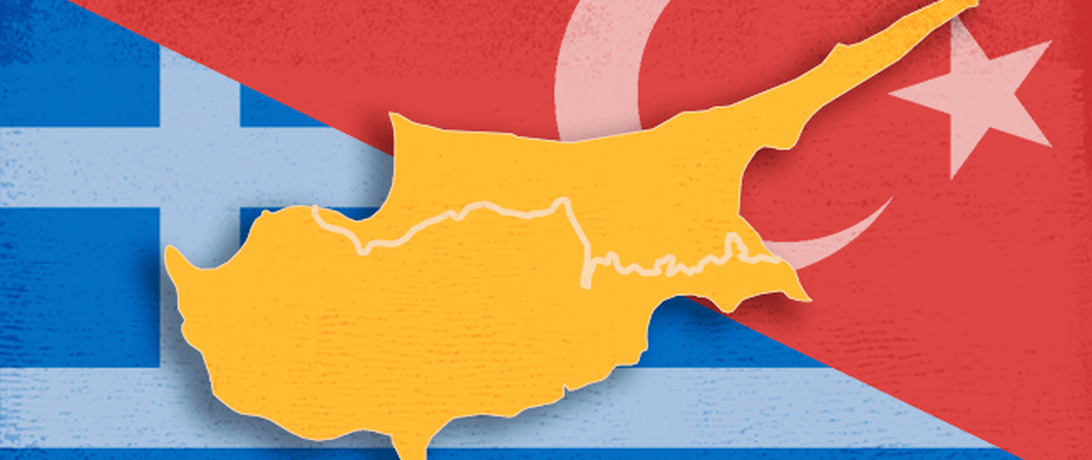

A certain antagonism rules the Mediterranean island of Cyprus: It sports the United Nations’ longest serving peacekeeping mission (established in 1964) and features Europe’s last divided city (Nicosia), but it is also a member state of the European Union (since 2004) and is in fact a popular tourist destination. However, the Greek and Turkish Cypriots have been in a diplomatic stalemate for decades.

Despite recurrent deadlocks and the tenacious pace of negotiations and meetings over the years, the two sides recognize that partition is no longer a viable solution. Unfortunately for both sides, however, a Cypriot solution negotiated by Greek and Turkish Cypriots seems virtually impossible. External factors tend to eclipse local efforts toward reunification.

As we learned in the first two blog posts on how new leaders can end interstate rivalries and domestic insurgencies, leaders often have flexibility to reshape policy, especially with regard to international disputes. The Cypriot example, though, suggests that leaders may run on a specific policy but fail to implement it. Why? Leaders could be hamstrung by international patrons that have a vested interest in the conflict, stymieing negotiations. In other words, leaders might be elected on a promise to resolve a crisis, but the facts on the ground prevent them from turning that promise into actionable change.

A case in point is the reelection in February 2018 of Greek Cypriot leader Nicos Anastasiades, although some might argue he was reelected more for his ability to maneuver Cyprus out of the financial misery that prompted its 2008 financial crisis rather than for his commitment to reunification. However, both Anastasiades and his Turkish Cypriot counterpart, Mustafa Akınc, have been longtime proponents of reunification under a bizonal and bicommunal federation.

The obstacles to a negotiated settlement are not only (or mainly) the key stakeholders on the island of Cyprus but some actors on the mainland, most notably Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. His reelection in July of this year will have major ramifications for both domestic and regional issues. Our REIGN data, the latest Freedom House Report on Turkey, and KOTO indicate that although the distribution of democratic regimes has grown substantially over time, especially in the Western Hemisphere, Turkey may have the superficial trappings of a democratic regime while internally it faces a steady decline in political rights and civil liberties. It will take time for the data to pick up on these trends so that we can make conclusive statements, but the speed at which Erdoğan has been proposing changes to the constitution that would grant him more presidential powers suggests that his turn to more authoritarian rule may also mean greater control in dictating terms to Cypriots.

Some consider him a wild card, others a lenient supporter of (or at least not a stark opponent to) reunification. However, Erdoğan caused unease and flat-out animosity against him among Turkish Cypriots during a recent visit to the northern part of the island that is only formally recognized as a state by Turkey. Currently, Turkish Cypriots are outnumbered by Turkish troops and emigrants from mainland Turkey. Moderate and secular, these Turkish Cypriots reject Erdoğan’s authoritarian rule and conservative views on Islam.

But as the Turkish Cypriots’ main—in fact only—guarantor, Erdoğan may bring some serious muscle to the decisions that will govern the future of Cyprus. His insistence on having sole decision-making power regarding Turkish Cypriots is primarily based on the fact that without Turkey’s involvement, northern Cyprus would struggle economically. Tying economic survival to security, Turkey continues to justify the presence of its troops by exploiting the current settlement that grants the UK, Turkey, and Greece the right to use military intervention.

Turkish Cypriots’ concerns are not completely unwarranted given the scale of intercommunal violence in the 1960s that eventually led to Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus in 1974. The violence and subsequent Turkish occupation triggered the exodus of Turkish Cypriots from the southern part to the north of the island. As a result, Turkey is less keen on reducing its military strength. But the proclivity to view the conflict through the lens of hyperbolic securitization runs deep on both sides and often overshadows issues that have more potential to be negotiated and settled, such as disputes over territories.

The closest the two sides ever came to an agreement was in 2004 when Secretary-General Kofi Annan developed a comprehensive peace deal. The Greek Cypriots voted against the deal in a referendum while the Turkish Cypriots approved it. In 2017, Secretary-General António Guterres brought the two sides back to the negotiation table, but the initiative subsequently failed due to diverging views on several agenda items. As of late, approaches toward resumption of talks between the two Cypriot leaders in April 2018 have been marred by disputes over a new set of challenges, including the exploitation of hydrocarbons near Cyprus’s territorial waters.

In sum, Greece’s and Turkey’s involvement in Cyprus will continue unabatedly. It is at times quite surprising given that both countries battle several domestic issues. Greece has endured an economic crisis for several years, and Turkey’s geostrategic role in the Syrian conflict and its crackdowns on opposition have drawn a lot of negative attention from the international community. One would think these issues might steer attention away from Cyprus and leave room for Cypriots to decide their own future. But while the European Union can exert pressure, for example by stalling Turkey’s accession to this body, and while the response by Turkish Cypriots is significant, leadership in other countries will continue to hold Cyprus hostage to its partition. At least for now.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights