Discussions about peace have tended toward idealism or theory, but it can be talked about as the subject of scientific inquiry.

Is a world without war possible? This question sounds like a philosophical question, and for many years it has been. As a result, discussions about peace have tended toward idealism or theory, and the idea that this question can be answered with modern social science has not been a part of the mainstream discussion. In fact, a developing body of research has treated this question as the subject of scientific inquiry, and the results of this research have provided new insights to the understanding of how peace can be achieved.

Is a world without war possible? This question sounds like a philosophical question, and for many years it has been. As a result, discussions about peace have tended toward idealism or theory, and the idea that this question can be answered with modern social science has not been a part of the mainstream discussion. In fact, a developing body of research has treated this question as the subject of scientific inquiry, and the results of this research have provided new insights to the understanding of how peace can be achieved.

Most people who hear the question “is a world without war possible” probably answer “no.” The history of humanity can be told as a history of war. From the classical age through the dark ages and into the middle ages, the renaissance, and modern history, warfare has always been a significant part of human history. Most observers would probably argue, as the realist school of international relations does, that the international system is determined first and foremost by power – particularly military power – and as a result, war is a fundamental part of the international system.

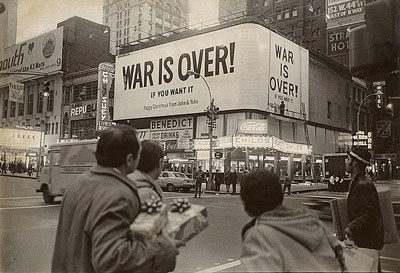

Other people may answer that yes, peace is possible. John Lennon and Yoko Ono famously rented billboards in Times Square in 1969 saying “War is over, if you want it.” The anti-war movement in the US and internationally has consistently rejected violence, and enormous numbers of people turned out to anti-war protests in the mid-2000s. Many of these activists would say that war is a conscious choice of politicians, and if decision makers were to reject military force as a tool of public policy then war would end.

Other people may answer that yes, peace is possible. John Lennon and Yoko Ono famously rented billboards in Times Square in 1969 saying “War is over, if you want it.” The anti-war movement in the US and internationally has consistently rejected violence, and enormous numbers of people turned out to anti-war protests in the mid-2000s. Many of these activists would say that war is a conscious choice of politicians, and if decision makers were to reject military force as a tool of public policy then war would end.

Both of these perspectives are rooted in individual analysis, interpretation of history, and the decision-making process that leads to war. They ultimately treat the question of whether a world without war is possible as a philosophical question: a question of human nature and how decisions are made. There is another way of thinking about this question, however. Seen from another perspective, the question of whether it’s possible that the world will eliminate war is an empirical question. It’s a question that can be informed, if not answered, by the trends in war and the causes of war over human history. Seen from this perspective, there’s a developing conclusion that peace is possible. Moreover, the social trends and pressures that are contributing to peace – or potentially undermining it – can be uncovered and addressed by research.

One Earth Future is interested in the connection between research and practice, and we wanted to explore whether this perspective on peace and security was a legitimate way to think about peace. In 2014, we held the first of our OEF Forum series on peace and security to bring together researchers, activists, members of the military, and government decision-makers for a two-day discussion. The goal of this conversation was to pose the question of whether peace is possible, and if so how it can be achieved. The consensus of this discussion was a firm conviction that contrary to the view of history that says that war is inevitable and constant, war is clearly affected by social institutions and structures and the world has been trending slowly and steadily in the direction of peace. If these trends are supported and extended, peace is possible. This is ultimately not a moral claim, but an empirical one: battle deaths and major wars have declined throughout history and throughout the 20th century, and so achieving peace is a question of reinforcing the drivers of this decline.

One Earth Future is interested in the connection between research and practice, and we wanted to explore whether this perspective on peace and security was a legitimate way to think about peace. In 2014, we held the first of our OEF Forum series on peace and security to bring together researchers, activists, members of the military, and government decision-makers for a two-day discussion. The goal of this conversation was to pose the question of whether peace is possible, and if so how it can be achieved. The consensus of this discussion was a firm conviction that contrary to the view of history that says that war is inevitable and constant, war is clearly affected by social institutions and structures and the world has been trending slowly and steadily in the direction of peace. If these trends are supported and extended, peace is possible. This is ultimately not a moral claim, but an empirical one: battle deaths and major wars have declined throughout history and throughout the 20th century, and so achieving peace is a question of reinforcing the drivers of this decline.

Our report, The Century of Peace?: Empirical Trends in Peace and Conflict develops what this extension and support may look like in practice. The existing pressures leading to peace are clear: economic development, human development, and global peacekeeping systems have all manifestly contributed to peace. If these systems are strengthened, there’s every reason to believe that the world may continue to trend towards peace. In addition, improving women’s engagement in economic and political life internationally, and in peacemaking specifically, can support peace both directly and indirectly through its influence on human development. Finally, participants raised the issue of norms and beliefs: the activist argument that violence is a choice has some merit, and the decision to use military force requires that people see such force as a legitimate tool. As the world continues to trend towards peace, more direct engagement with the norms and beliefs that legitimize violence will be an important contributor to peace.

Our report, The Century of Peace?: Empirical Trends in Peace and Conflict develops what this extension and support may look like in practice. The existing pressures leading to peace are clear: economic development, human development, and global peacekeeping systems have all manifestly contributed to peace. If these systems are strengthened, there’s every reason to believe that the world may continue to trend towards peace. In addition, improving women’s engagement in economic and political life internationally, and in peacemaking specifically, can support peace both directly and indirectly through its influence on human development. Finally, participants raised the issue of norms and beliefs: the activist argument that violence is a choice has some merit, and the decision to use military force requires that people see such force as a legitimate tool. As the world continues to trend towards peace, more direct engagement with the norms and beliefs that legitimize violence will be an important contributor to peace.

The key conclusion from our discussion was that a world without war is possible. This is both a conclusion from the conversation, and the starting point for more discussion. The three pathways to peace we identified last year are broad, and point to general recommendations instead of specific ones. The discussion will continue at the 2015 OEF Forum in Dedham Massachusetts next week, and perhaps will identify more specific recommendations for how peace can be achieved. What is more important, however, is the simple fact that there is a developing awareness that peace is possible, through a technical, social science approach. If the global community can continue to develop our understanding of the causes of peace, and continue the inexorable growth of development and systems that support peace, then a world without war may not only be possible but in fact inevitable.

The key conclusion from our discussion was that a world without war is possible. This is both a conclusion from the conversation, and the starting point for more discussion. The three pathways to peace we identified last year are broad, and point to general recommendations instead of specific ones. The discussion will continue at the 2015 OEF Forum in Dedham Massachusetts next week, and perhaps will identify more specific recommendations for how peace can be achieved. What is more important, however, is the simple fact that there is a developing awareness that peace is possible, through a technical, social science approach. If the global community can continue to develop our understanding of the causes of peace, and continue the inexorable growth of development and systems that support peace, then a world without war may not only be possible but in fact inevitable.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights