OEF’s goal is ultimately the elimination of war. In order to achieve this admittedly lofty goal, we need to have a working theory of the causes of war and how we can help to disrupt them. Fortunately, there is a large body of research in “peace science” and, more broadly, political science. In developing our theory, our challenge wasn’t having too little information - it was coming up with a way of analyzing all of the research out there and developing a theory of war useful to our work.

One Earth Future Foundation’s goal is ultimately the elimination of war. In order to achieve this admittedly lofty goal, we need to have a working theory of the causes of war and how we can help to disrupt them. Fortunately for us, a large body of research in “peace science” and, more broadly, political science has extensively dug into this question. In developing our theory, our challenge wasn’t having too little information - it was coming up with a way of getting our arms around all of the research out there and developing a theory of war useful to our work.

Theories are ultimately developed with a specific goal: they’re designed to be useful for some purpose, even if that purpose is as broad as driving our collective scientific understanding of a particular phenomenon. In our case, we needed to systematize our way of thinking about the drivers of war that provided a platform for designing programs that could disrupt them. To do that, we ultimately settled on two ways of thinking about the root causes of conflict.

One is issue-based, identifying the relationships between different conflict drivers that impact a particular issue, and gives us a way to structure our work in terms of what’s needed for long-term success. One fundamental conclusion from the existing research on war is that the causes of war are always complex: war can be triggered by specific crises, but the root causes always bring in multiple different issues creating the context for violence. Consider the case of the ongoing war in Syria: the roots of this conflict are a messy mixture of demands for democracy, violence by the Assad regime, and factionalized international support as well as historical and regional pressures. It’s not really feasible to reduce the causes of the conflict to any single pressure. So our first way of thinking about conflict looks at what those pressures might be and how they interact. We wanted to develop a way of collecting the existing research that let us capture the big picture. At the same time, such a framework has to acknowledge the different dynamics of war in all the different ways that war plays out whether within, between, or across countries.

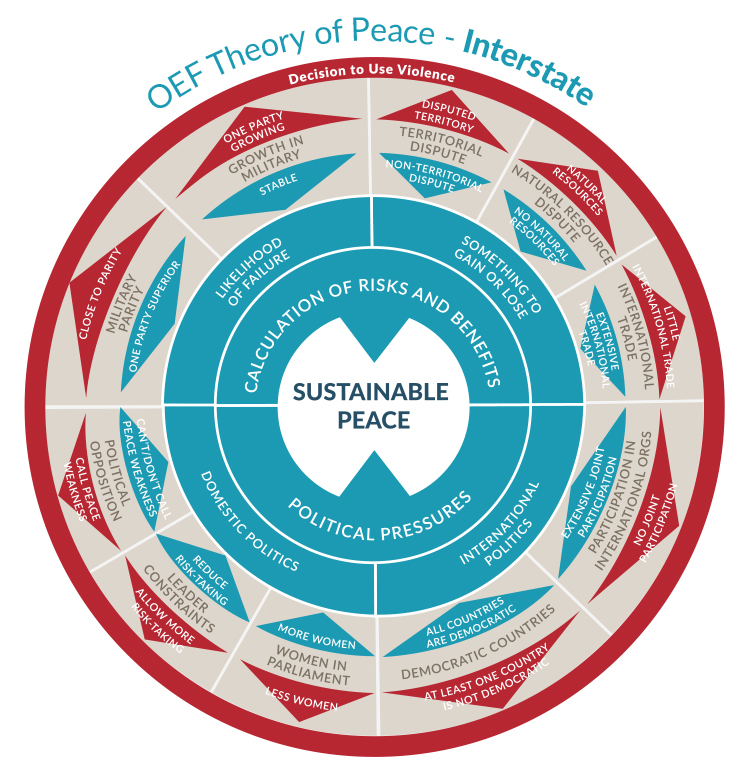

Our theory of war is that, generically, across the different levels and types of conflict, you can identify issues that create pressures for war and pressures that reduce it. War is more likely when the issues being disputed - the grievances, or the disagreement between states - are more important to the potential combatants. War is more likely when people or countries have less to lose, so the current circumstances play into it. Similarly, war is more likely when people or countries feel that it’s likely to be successful, and especially when they don’t see any other pathway to getting their needed goals. Beliefs, or norms play into this as well: when people are accustomed to the idea that violence is a tool for political dispute or otherwise believe it’s appropriate, it’s easier to convince people that violence is necessary.

The specific ways this plays out are different from context to context. Considering conflict within countries, these pressures come out in questions of overall quality of life - including issues such as economic development, optimism about the future, and access to education and other social services - and also questions around the legitimacy of governance. The latter includes perceptions about transparency and just government as well as issues of access and inclusion, and norms about whether violence is acceptable or not.

In war between states, different issues operate under the same basic framework of pressures towards and away from the use of violence. Questions of the strategic value of war, in terms of national or political goals, and also questions about how effective the war is likely to be, appear to be pressing in understanding interstate war. War is more likely when the issues are zero-sum and important, and when domestic political pressures either reward a leader for war or when they don’t constrain him (or her, although in general governments with more women in leadership are less likely to support the use of military force). War is also more likely when the outcome is more in doubt.

Finally, we see internationalized war - war within a country supported by other countries - as a hybrid of the two in which a country uses a potential conflict in another country to advance some of the goals otherwise advanced by interstate war.

Considering the balance of pressures towards and away from internationalized war is exceptionally dangerous because it allows countries to export all the negatives and most of the risks of war to other countries, while retaining much of the benefits. Through this lens it’s perhaps not surprising that internationalized wars are becoming more common, and are much harder to end.

The second way we think about conflict is chronological, and provides a framework for identifying points of engagement in evolving conflicts. We also draw a distinction between structural drivers of conflict and the actual outbreak of violence, often in response to short-term crises or events. We divide drivers of conflict into structural pressures - the long-term conditions which increase the risk of violence - and crisis moments that may trigger an outbreak of war.

In the first case, long-term or structural pressures include issues that increase people’s willingness to use violence, through changes to the conditions we describe in more detail below. Those pressures may exist for a long time without active violence though and so separately we consider the situations that can trigger war. These crises can include a strategic choice by some actor to launch an attack or a coup, or an escalating pattern of strategic decisions that create a feedback cycle for war.

This is all moderately complicated, but that’s because conflict is complicated and coming up with a “unified theory of war” is challenging. The key takeaway from OEF’s work is that conflict always comes from multiple pressures - multiple issues and also both long-term and short-term problems. This means that peacebuilding, if it’s to be successful, has to work across all of the relevant timing and issue spaces all together. Weaknesses in any one issue will undermine the others and undermine peacebuilding effectiveness.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights