The expectation is that state and non-state actors should be on the same team, but in reality, they are often playing against each other.

Contemporary global governance involves a complex interplay between state and non-state actors. While the expectation remains that they should be on the same team, in reality they are often playing against each other. State actors are national governments or large bureaucracies like the United Nations. On the other hand, the term “non-state actors” casts a wider net. Its members range from private organizations such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, to transnational businesses like Apple or Walmart. An extended definition would include bodies that represent special interest groups such as professional organizations, and chambers of commerce.

But what sorts of organization are best equipped to solve international problems – the large-scale, state-led organizations or the smaller and more nimble NGOs? While some stand firmly behind large bureaucracies like the UN, others wonder why the often-inefficient behemoths like the UN should take the lead role in addressing global issues.

But what sorts of organization are best equipped to solve international problems – the large-scale, state-led organizations or the smaller and more nimble NGOs? While some stand firmly behind large bureaucracies like the UN, others wonder why the often-inefficient behemoths like the UN should take the lead role in addressing global issues.

Craig N. Murphy argues that non-state actors have actively participated in multilateral engagements since as early as the 19th century and should maintain their influence in global governance. In Europe, private associations of professionals and social activists would meet to set voluntary international standards at the same time - and often in the same place - as public officials set multilateral engagements.

Many non-state actors – some NGOs especially – share the UN’s goals but are more effective and efficient in addressing global crises, conflict resolution, and sustainable development. This is because NGOs are closer to ground realities, more flexible, and able to provide focused expertise in areas where the UN might only have a general interest. And unlike the UN, they are less politically constrained.

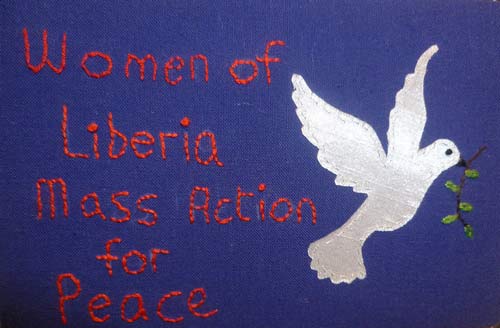

The recent Ebola crisis and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) sluggish response demonstrate this clearly. Until the crisis, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was the sole NGO with experience treating the disease. It was also the first international organization to recognize the imminence of an epidemic. However, its initial warnings were not only ignored, but also trivialized by the WHO, which accused MSF of exaggeration and scaremongering. Another example can be found in the actions of a local non-state group in Liberia. The Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace campaign helped catalyze the truce between then-president Charles Taylor and opposition rebel groups that brought an end to the four-year civil war. These women were able to start a dialogue between actors by identifying themselves in the revered roles of mothers, wives and sisters, using religious language and refusing to discuss politics or take sides. They were arguably more effective than UN peacekeepers or other UN actors who were deployed in the region.

The recent Ebola crisis and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) sluggish response demonstrate this clearly. Until the crisis, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was the sole NGO with experience treating the disease. It was also the first international organization to recognize the imminence of an epidemic. However, its initial warnings were not only ignored, but also trivialized by the WHO, which accused MSF of exaggeration and scaremongering. Another example can be found in the actions of a local non-state group in Liberia. The Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace campaign helped catalyze the truce between then-president Charles Taylor and opposition rebel groups that brought an end to the four-year civil war. These women were able to start a dialogue between actors by identifying themselves in the revered roles of mothers, wives and sisters, using religious language and refusing to discuss politics or take sides. They were arguably more effective than UN peacekeepers or other UN actors who were deployed in the region.

A common criticism of examples like these is that they are isolated and non-replicable. Indeed, it would be very alarming if non-state actors were the only form of governance, functioning without any structure or real accountability. While local responses to local problems are crucial, they are unable to address increasingly trans-boundary issues that require coordinated state action, such as climate change, international terrorism and economic instability. Thomas Weiss and Dan Plesch show that the big problems the world faces today require coordinated international action that can only be provided by actors who benefit from global legitimacy, like the UN.

Furthermore, it is easy to forget the UN’s past successes. These include the negotiation of 172 peace settlements since 1945. The creation of the UN Peacekeeping forces has allowed for multilateral armed action, where unilateral military interventions may be misperceived as invasions. 71 such peacekeeping missions have been undertaken since 1948. Perhaps most significantly, the UN firmly put poverty alleviation and international development on the world agenda. It is difficult to imagine a time when development wasn’t a priority for the international community, and this is largely thanks to the various agencies of the UN.

While states, alone or collectively, can be powerful actors in addressing national and global problems, they should acknowledge that they can’t always go it alone. Non-state actors have a crucial role to play in solving problems and should be included in the agenda-setting, execution and monitoring of programs. Arbitrary exclusion of non-state actors makes governance less effective and perhaps less responsive to global needs. While the UN makes efforts to coordinate actions with non-state actors, such as through the creation of the UN Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations and consultative status provisions for NGOs, there is an underlying assumption that NGOs will pander to the political agendas of the members of the UN. Arbitrary exclusion of non-state actors makes governance less effective and problems less likely to be solved. In order to optimize contemporary global governance, the UN needs to accept dissonant views and strategies that have proven to be successful. By advancing the agendas of NGOs, the UN can lend authority to effective non-state actors and continue to be a legitimate leader in the international sphere.

While states, alone or collectively, can be powerful actors in addressing national and global problems, they should acknowledge that they can’t always go it alone. Non-state actors have a crucial role to play in solving problems and should be included in the agenda-setting, execution and monitoring of programs. Arbitrary exclusion of non-state actors makes governance less effective and perhaps less responsive to global needs. While the UN makes efforts to coordinate actions with non-state actors, such as through the creation of the UN Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations and consultative status provisions for NGOs, there is an underlying assumption that NGOs will pander to the political agendas of the members of the UN. Arbitrary exclusion of non-state actors makes governance less effective and problems less likely to be solved. In order to optimize contemporary global governance, the UN needs to accept dissonant views and strategies that have proven to be successful. By advancing the agendas of NGOs, the UN can lend authority to effective non-state actors and continue to be a legitimate leader in the international sphere.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights