From sandwiches to sushi, tuna is a global staple. World tuna catch is worth more than $42 billion annually, making the tuna industry a giant in the fishing world. It supports millions of jobs and provides food security for people in developed and developing countries alike.

From sandwiches to sushi, tuna is a global staple. World tuna catch is worth more than $42 billion annually, making the tuna industry a giant in the fishing world. It supports millions of jobs and provides food security for people in developed and developing countries alike. So when the conservation status of one species suddenly changes from sustainably fished to overfished, alarm bells ring across the world and, in this case, especially in the Indian Ocean.

In November 2015, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) listed one of the Indian Ocean’s highest value fish, yellowfin tuna, as “overfished.” This was a blow to fishing economies throughout the Indian Ocean that depend on tuna as an export. Over the entire Indian Ocean, yellowfin tuna accounts for 45% of tuna landings and is worth US $1.2 billion when sold off the boat (before processing). After moving through a value chain that often lands it on dinner plates thousands of miles from where it was caught, the total value of Indian Ocean tuna triples.

In countries with small-scale tuna fisheries, the rapid decline of yellowfin populations could trigger a significant downturn in their fishing economies. For example, in Somalia, yellowfin tuna makes up 15% of artisanal catch. This one species contributed US $6.5 million to the Somali economy in 2010. If this fish were to disappear, the lost revenue would be detrimental to the livelihoods of Somali artisanal fishers.

How did this happen?

Tuna fishing has a long history dating back thousands of years. However, the Indian Ocean’s proliferation as a global seafood source began in the 1980s with the introduction of highly efficient fishing gear. Between the mid-1950s to around 1980, annual catch of yellowfin tuna in the Indian Ocean was a fairly constant 20,000 to 60,000 tons, caught mostly by Asian longlining vessels. But beginning in 1982, annual tuna catch in the Indian Ocean ballooned, reaching 900,000 tons by 1999.

Tuna fishing has a long history dating back thousands of years. However, the Indian Ocean’s proliferation as a global seafood source began in the 1980s with the introduction of highly efficient fishing gear. Between the mid-1950s to around 1980, annual catch of yellowfin tuna in the Indian Ocean was a fairly constant 20,000 to 60,000 tons, caught mostly by Asian longlining vessels. But beginning in 1982, annual tuna catch in the Indian Ocean ballooned, reaching 900,000 tons by 1999.

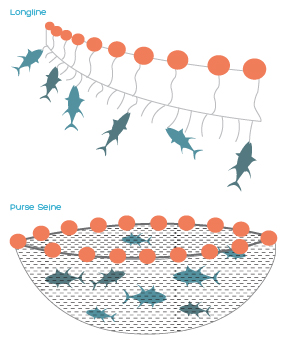

Global expansion and technological developments had a major impact on tuna fishing. In the early 1980s, European purse seine vessels entered the scene. This highly efficient fishing method uses a large net to surround an entire school of tuna, rather than catching one fish per hook as on a longline. Purse seiners grew even more efficient with the use of fish aggregating devices (FADs). These are floating structures that attract fish, making it easier to surround them with the large net. The rapid increase in purse seine vessels, coupled with an increase in fishing effort by longliners, resulted in a dramatic increase in tuna catch to 350,000 tons per year.

These fishing fleets are fulfilling a ravenous global appetite for tuna. As the demand for tuna has grown, so has the range of these vessels. After decades of overfishing in their own waters, fishers are expanding beyond their home countries’ depleted ocean resources to fish in the waters of other countries that lack the ability to manage or prevent foreign fishing. For countries that are still developing their fishing industries, foreign fishing vessels are competing with local fishers for decreasing resources. In Somali waters, foreign fishers extract three times more fish than domestic fishers do.

What are the solutions?

The wakeup call by the IOTC may be forcing a change. The declaration of yellowfin as overfished has forced the tuna fishing industry to take pause. Even companies whose incentives are profits rather than conservation are coming to recognize that continuing to overfish yellowfin will mean losing their industry forever. In response, fishing companies and supermarkets are partnering with NGOs in a call for a 20% reduction in catch.

Their cooperation is pressuring the IOTC to create better harvest control rules for yellowfin and other heavily exploited species such as skipjack. Last month’s session of the IOTC resulted in agreement on a 20% reduction in skipjack and 10% reduction in yellowfin catch across the Indian Ocean. This is an excellent first step. However, reporting catch to the IOTC is voluntary and it is estimated that one third of catch goes unreported. Without full regional compliance for reporting, the IOTC cannot accurately measure how many fish are being removed. Therefore, a decrease in the allowed catch has little meaning until every country fishing for yellowfin tuna in the Indian Ocean fully reports its catch.

For developing countries that are trying to grow their fisheries sectors, stopping the overfishing of an important species like yellowfin is crucial. Their ability to grow and compete on the global market depends on the industrial fleet leaving some fish in the ocean for them to catch and sell. Regional cooperation and compliance is the only way to ensure everyone can get a piece of the tuna steak.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights